|

Threat to Site |

| Why the prison is

at risk, and what can be done about it |

| |

|

Camp History |

| History of the

Johnson's Island Prisoner of War Depot |

| |

|

|

|

|

Camp History

Johnson's Island Prisoner

of War Depot

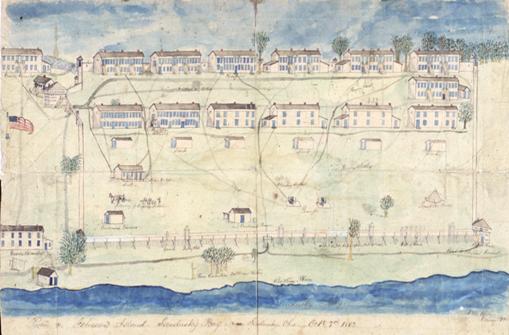

From April of 1862 until

September of 1865, over 10,000 Confederates passed through

Johnsonís Island Civil War Military Prison leaving behind an

extensive historical and archaeological record. Many of

these officers recorded in journals or diaries the day to

day happenings, emotions, and conditions they were enduring.

They also spent many hours writing letters, collecting

autographs from prisoners, and sketching maps. These

documents give vast insight into what prison life was like,

as well as the personal conflicts and hardships encountered

among families and friends during the Civil War.

The 16.5 acre Johnsonís

Island Prison Compound contained 13 Blocks (12 as prisoner

housing units and one as a hospital), latrines, sutlerís

stand, 3 wells, pest house, 2 large mess halls (added in

August, 1864) and more. The Blocks were two stories high and

approximately 130 by 24 feet. There were more than 40

buildings outside the stockade (barns, stables, a lime kiln,

forts, barracks for officers, a powder magazine, etc.) used

by the 128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry to guard the prison.

The two major fortifications (Forts Johnson and Hill)

protecting Johnson's Island were constructed over the

1864/65 winter, and were operational by March of 1865. The 16.5 acre Johnsonís

Island Prison Compound contained 13 Blocks (12 as prisoner

housing units and one as a hospital), latrines, sutlerís

stand, 3 wells, pest house, 2 large mess halls (added in

August, 1864) and more. The Blocks were two stories high and

approximately 130 by 24 feet. There were more than 40

buildings outside the stockade (barns, stables, a lime kiln,

forts, barracks for officers, a powder magazine, etc.) used

by the 128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry to guard the prison.

The two major fortifications (Forts Johnson and Hill)

protecting Johnson's Island were constructed over the

1864/65 winter, and were operational by March of 1865.

The Hoffman Battalion

with other companies that formed the 128th Ohio Volunteer

Infantry became the official guards of the prison under the

charge of William S. Pierson, former mayor of Sandusky.

Because of his cruelty to prisoners and his inability to

handle problems and keep the prison in good order, he was

replaced. On January 18, 1864 Brigadier General Harry D.

Terry replaced Pierson. A few months later, on May 9, 1864,

Colonel Charles W. Hill took command at Johnson's Island,

remaining as such until the end of the war.

As prisoners of war, they

daily faced how to cope with their situation, whether to

resist, to survive, or to assimilate by taking the Oath of

Allegiance. Their choices resulted in a variety of

activities taking place. Those contemplating escape spent

time preparing...whether disguising as a guard, walking

across the frozen lake into Canada, or tunneling from a

latrine... any idea took great planning and time to

orchestrate. Some prisoners used their talents and limited

resources to pass the time by carving rings, broaches, and

other jewelry out of hard rubber, bone, and shell. Reading,

especially newspapers was important to keep informed of the

latest victories and defeats of the War, government actions,

and news of exchanges. As prisoners of war, they

daily faced how to cope with their situation, whether to

resist, to survive, or to assimilate by taking the Oath of

Allegiance. Their choices resulted in a variety of

activities taking place. Those contemplating escape spent

time preparing...whether disguising as a guard, walking

across the frozen lake into Canada, or tunneling from a

latrine... any idea took great planning and time to

orchestrate. Some prisoners used their talents and limited

resources to pass the time by carving rings, broaches, and

other jewelry out of hard rubber, bone, and shell. Reading,

especially newspapers was important to keep informed of the

latest victories and defeats of the War, government actions,

and news of exchanges.

Prisoners could receive

packages and mail. The mail was inspected and the parcels

were searched and often damaged or depleted before the

prisoner received them. Consequently prisoners often relied

on the sutler store to buy sewing supplies, ink, stationery,

clothes, food, combs, toothbrushes, etc. These items could

be purchased until late in the war when food, along with

other items, were no longer permitted to be sold by the

sutler.

The prisoners on

Johnsonís Island, along with most of the soldiers that

fought in the Civil War endured harsh winters, food and fuel

shortages, disease, along with the mental anguish of

uncertainty about their families and their own futures.

Current research suggests that close to 300 prisoners died

on Johnsonís Island during the war. The prisoners on

Johnsonís Island, along with most of the soldiers that

fought in the Civil War endured harsh winters, food and fuel

shortages, disease, along with the mental anguish of

uncertainty about their families and their own futures.

Current research suggests that close to 300 prisoners died

on Johnsonís Island during the war.

After the Civil War, most

of the buildings on Johnsonís Island were auctioned off. The

land was used for farming, and quarrying started in the late

1800ís. The resort business began around then also, but

eventually failed. Residential building began in the 1950ís

allowing private residents to enjoy waterfront properties.

In 1990, Johnsonís Island was designated as a National

Historic Landmark recognizing its significance in the Civil

War as one of the premier Union prisons. The Confederate

Cemetery, located on Johnsonís Island is currently the only

publicly available part of the prison. A portion of the

prison compound and all of Fort Johnson have been set aside

for long term preservation by the current landowner. |